Could Celestina Sommer have been inspired to cut her daughter’s throat by another child murder? I believe that it’s at least possible.

In the last episode of this story, I mentioned that the two policemen, Inspector Hatton and Sergeant Edward Townsend, and Celestina’s husband Charles Sommer went to see her sister, Elizabeth Grobe.

This was still on Monday, 18 February, 1856, the day Charles and Celestina Sommer were charged at Clerkenwell Police Court. They’d just been to see my 3x great grandmother, Julia Harrington, who’d brought up little Celestina Christmas from birth.

But what I’m looking at today is almost a throwaway comment. Here it is, from the Reading Mercury of 23 February:

Elizabeth and Charles Grobe lived at 16 Murray Street, now called Murray Grove. Next door to them, at no 17, another murder had been committed. Mary McNeil (McNeill, M’Neil in some newspapers) had cut the throats of her two illegitimate sons. Well, OK, you may say, that was a sad and not uncommon crime in Victorian days.

Elizabeth and Charles Grobe lived at 16 Murray Street, now called Murray Grove. Next door to them, at no 17, another murder had been committed. Mary McNeil (McNeill, M’Neil in some newspapers) had cut the throats of her two illegitimate sons. Well, OK, you may say, that was a sad and not uncommon crime in Victorian days.

But here’s some more information about the McNeil murder, from the Morning Chronicle of 1 December, 1855:

Here we have ‘intense and painful’ excitement outside the police court as a well dressed, attractive woman is charged with killing two of her children (one was in the country at the time).

Here we have ‘intense and painful’ excitement outside the police court as a well dressed, attractive woman is charged with killing two of her children (one was in the country at the time).

As Lloyd’s Weekly said on the following day:

A respectable, genteel person of 25, mother of illegitimate children, who cut their throats with a razor. Is this beginning to look familiar?

A respectable, genteel person of 25, mother of illegitimate children, who cut their throats with a razor. Is this beginning to look familiar?

Linton St (top left) and Murray St (bottom right) in 1861 *

The news of the McNeil murder was widely reported in the newspapers. It would’ve been the talk of the area, and Murray St was fairly near Linton St, where the Sommers lived.

I’ve shown them on this 1861 map, with Linton St in pale blue at the top left and nos 16 (green) and 17 (red) Murray St bottom right.

And it’s inconceivable that members of the Christmas family, including the elder Celestina, wouldn’t have spoken and thought about a murder which was committed next to where one of them lived.

But you’re canny readers and that’s not enough to convince you that this murder could have any connection with the cutting of little Celestina Christmas’s throat by her own mother. Me neither, until I read more about the McNeil murder case.

Murray St (Grove). Nos 16 and 17 were just beyond where the orange-lidded bins are in this photo. © Frances Owen 2015

Briefly, what happened was that Mary McNeil was the mistress of a man who was the father of her three young children. He provided them with enough money to live comfortably. However after the birth of her last child, Mary changed. She was ‘wretched and miserable’, hit her children, and complained that they had no decent clothes to wear. Her lover, James Williams, had taken one of the children away after she’d threatened to harm it.

At the time, people said that she had ‘milk fever’, which is actually a term for mastitis. These days, I imagine, we’d describe what she suffered from as postnatal depression.

On November 29, 1855, Mary’s upstairs neighbour found a cash box on the kitchen stairs, partly covered by a gown. It belonged to Mary, and the neighbour took it to her door, but when he went to give it back to her he saw her baby son ‘lying on the bed… with its throat cut and in a pool of blood.’ He dropped the box and fetched a policeman, who found the four-year-old boy also dead, his throat slit ‘from ear to ear’. By his head lay the razor Mary’d used to kill the boys.

Mary was sitting, ‘rocking herself to and fro’ and wailing “oh, what have I done?” She admitted the murder. The Bath Chronicle added this odd remark about the cash box:

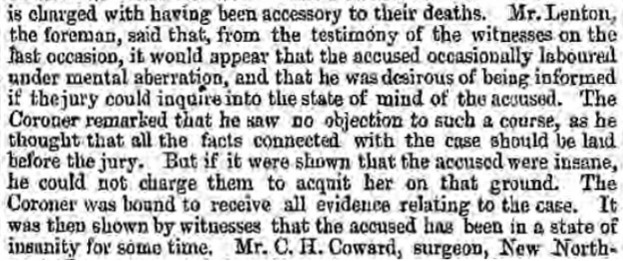

During the court proceedings that followed, her mental health was mentioned several times. Interestingly, the jury at the coroner’s inquest was very concerned about it. Here’s The Era, published on 9 December:

During the court proceedings that followed, her mental health was mentioned several times. Interestingly, the jury at the coroner’s inquest was very concerned about it. Here’s The Era, published on 9 December:

It continues:

It continues:

I’ve no idea whether the cash box has any echoes in Celestina’s locked box with three clasps, which her servant Rachel Mount thought important enough to mention, or whether Celestina’s bizarre behaviour in wearing bloodstained clothes after she’d murdered her daughter is connected with Mary McNeil’s story in any way. But they’re more odd coincidences.

I’ve no idea whether the cash box has any echoes in Celestina’s locked box with three clasps, which her servant Rachel Mount thought important enough to mention, or whether Celestina’s bizarre behaviour in wearing bloodstained clothes after she’d murdered her daughter is connected with Mary McNeil’s story in any way. But they’re more odd coincidences.

The emphasis on Mary McNeil’s mental state at the time she killed her children is much more obviously relevant. In spite of the awfulness of what Mary had done, there seemed to be a feeling of sympathy for her, and a reluctance to find her guilty. And this, I think, is the important point.

Mary McNeil was tried for wilful murder at the Old Bailey (Central Criminal Court) on Wednesday, 9 January, 1856. The prison surgeon, John Rowland Gibson, testified: “my opinion decidedly is, that she was of unsound mind at the time she committed the act.”

Mary’s mother confirmed that her husband, Mary’s father, “was sent to a lunatic asylum in consequence of his deranged state of mind—he was taken to Grove-hall Institution, and from there was removed to Bethlehem Hospital.”

And the court found her ‘Not guilty, being insane. To be detained until Her Majesty’s pleasure be known.’ Two other women were acquitted of murdering their children on the same day.

Mary McNeil and two other women acquitted of murder – Wells Journal report

Celestina’s behaviour has already been seen to be unexpected at times. In the eyes of Victorian society, for a respectable young unmarried girl to become pregnant was surely a sign of something wrong with her. Daughters were locked away in asylums for it. And as you’ll see in another post, Celestina was to act in a very bizarre way after her arrest.

Is it possible that she read about Mary McNeil’s sentence and thought that she had found a way to get rid of the unwanted child who she claimed was telling lies about her and causing quarrels between her and her husband?

The facts are these: on Wednesday, 9 January, 1856, Mary McNeil, next door neighbour of Celestina’s sister, was acquitted of murdering her illegitimate sons by cutting their throats. The newspapers reported the verdict widely over the next few days.

On Thursday, 7 February, Celestina Sommer took her illegitimate daughter away from Julia Harrington’s house, telling Julia that she’d found the girl a place to work – though this wasn’t true. On Saturday, 16 February, she cut Celestina Christmas’s throat.

If it’s a coincidence, it’s a very creepy one. What do you think?

I’ve written about my quest to find where 16 and 17 Murray St were over on the Worldwide Genealogy blog. I’ve also added another post here, which will give you an idea of what 16 and 17 might’ve looked like.

* Picture credits:

Newspaper extracts: The British Library Board, via Findmypast

Cross’s 1861 map of Murray St and Linton St: Mapco

Photograph of Murray Grove: © Frances Owen and A Rebel Hand, 2015. If anyone wants to re-use it that’s fine, if you ask me first! And attribute it, with a link, please. See copyright policy in the right-hand side bar

Catch up with A Christmas tale:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Part 19

Pingback: Celestina’s life in Millbank Prison: a Christmas tale pt 22 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Will Celestina hang? A Christmas tale pt 20 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Broadside ballads about Celestina: a Christmas tale pt 19 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina’s trial – verdict and sentence: a Christmas tale pt 18 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina Sommer’s trial for murder: a Christmas tale pt 17 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina at the Old Bailey: a Christmas tale pt 16 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina in Newgate Prison: a Christmas tale pt 15 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: New evidence against Celestina: a Christmas tale pt 14 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A mob at the inquest: a Christmas tale pt 13 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: The inquest in the pub: a Christmas tale pt 12 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A Christmas bonus | A Rebel Hand

I suppose there may have been mental instability but it sounds to me like Celestina is taking advantage of the findings of the other case copying it.

LikeLike

That’s my guess, Kerryn. Copying cutting the children’s throats and then hoping to be acquitted because she was ‘insane’ or had ‘occasional insanity’.

LikeLike

Certainly a weird coincidence.

LikeLike

It certainly is, Pauleen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Christmas tale: part 1 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A Christmas tale pt 2: The first Celestina | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A Christmas tale pt 3 – baby Celestina and the Harringtons | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A Christmas tale pt 4 – what next for Celestina Elizabeth? | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Christmas turns to Sommer: A Christmas tale pt 5 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A horrible and mysterious murder: a Christmas tale pt 6 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: The body in the cellar: a Christmas tale pt 7 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: The murder of Celestina Christmas: a Christmas tale pt 8 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Who killed Celestina? A Christmas tale pt 9 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Julia Harrington’s evidence: a Christmas tale pt 10 | A Rebel Hand

Well done for spotting this connection – did Celestina think she could copy Mary McNeill and get away with it?

LikeLike

Good question, Anne. At first I thought that this was just a gruesome coincidence, but the more I looked into the Mary McNeil case the more connections I saw. The evidence (which I’ll write about in a future post) certainly shows that Celestina thought she could get away with it, and, while I can’t prove that she copied Mary, the records do point that way.

LikeLike