Where’s the obvious place for a Victorian coroner to hold an inquest into the cause of death of a murdered child?

The pub, of course.

Inquest in a house (©Lewis Walpole Library via London Lives)

No, really. It’s not as daft as it may seem. Some inquests into ‘suspicious’ deaths could be held in the building where the person died, but in 1860s London there wouldn’t have been many public places large enough to hold an inquest. As well as the coroner, there would be a twelve-man jury, one or more witnesses, perhaps a surgeon, and the hangers-on: the gentlemen of the press and the curious public.

A private room at a pub, inn or tavern was ideal. This building was one of the centres of local society, along with the church or chapel. Though easy access to beer, gin and tobacco might not have helped the sobriety of the proceedings.

As Charles Dickens, who’d been at an inquest and wasn’t unfamiliar with London crime, wrote in Bleak House: ‘The Coroner frequents more public-houses than any man alive.’

Thomas Wakley holding an inquest (via The Lancet)

The medical journalist and biographer Samuel Squire Sprigge had more to say: ‘The taint of the tavern-parlour vitiated the evidence, ruined the discretion of the jurors, and detracted from the dignity of the coroner. The solemnity of the occasion was too generally lightened by alcohol… where the majesty of death evaporated with the fumes from the gin of the jury.’

This description was of the sort of inquest which took place before the reforming influence of his subject, Thomas Wakley, who was the coroner for West Middlesex (which included Islington and Finsbury) as well as a founding editor of the medical journal The Lancet and an MP. Wakley’s a fascinating man, and might’ve been the coroner at the inquest into little Celestina Christmas’s murder… but on Wednesday, 20 February 1856, he was elsewhere and his deputy, George Smith Brent, was in charge of the event.

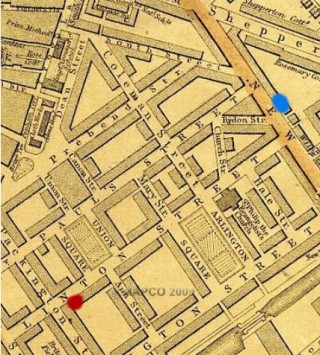

North Pole Tavern, near Linton St, 1868 map *

It was held four days after Celestina was murdered, and three days after her body was found. Inquests usually took place within 48 hours. With no refrigerated morgues, speed was necessary, but perhaps the kitchen at the Sommers’ house in Linton St, where the body was left, was cold enough in late February to stop too much decomposition. Let’s hope so for the sake of everyone involved.

The pub or inn chosen for an inquest was usually near where the death had taken place, and, as I’ve mentioned, it needed to have enough space for jury, witnesses and onlookers. Celestina’s inquest was held at the North Pole Tavern, 188-90 New North Rd, just round the corner from Linton St. On the 1868 map on the right I’ve marked the pub in blue, and 18 Linton St in red.

I’d have liked to visit it to get an idea of the size of the place (honest! No other reason!) but at the time I’m writing this it’s being refurbished. From photos I’ve seen of the inside it certainly looks large enough.

The North Pole © David Anstiss *

But before the inquest took place, something very important had happened.

Celestina Sommer had confessed to the murder.

I haven’t been able to work out from the newspaper reports exactly when she confessed, but it seems to have been after the police went with her husband, Charles Sommer, and my ancestor Julia Harrington to see poor little Celestina Christmas’s body at Linton St. Once the body’d been identified, there was very little reason to pretend that it was an unknown child’s.

Celestina also confessed that she’d used a knife to cut her daughter’s throat; but the police hadn’t been able to find it yet. There seems to be some mystery or significance attached to the murder weapon apart from its importance as evidence.

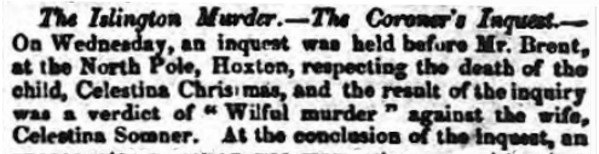

The inquest itself seems to have been straightforward, with no special pleading from the jury as there had been in Mary McNeil’s case (which I looked at two posts ago). There was little fuss in the newspapers. Here’s the Wiltshire Independent:

With such a verdict, the coroner’s only option was to make out a warrant for her to be committed to Newgate Prison to await her trial.

There’s one more thing to mention before I end this post.

Although the jury at the inquest didn’t seem to show any sympathy for Celestina Sommer, the crowd of spectators did. Spectacularly. I’ll write about that next time.

This post is long enough already, and I could’ve written so much more. But if you’re interested in more information about the history of coroners’ inquests in the mid-19th century, and indeed Victorian crime, here’s some further reading:

London Lives – a wonderful website, full of fascinating facts about crime in the capital

Coroners in North London

Coroners’ registers for early 1856 (TMA)

LMA‘s leaflet 41, Coroners’ records for London and Middlesex and their Register of inquests held by coroner for Western District, Middlesex (downloadable PDFs. I can’t link to them but just do a search)

Getting Away with Murder? Homicide and the Coroners in Nineteenth-Century London Mary Beth Emmerichs

Bodies of Evidence: Medicine and the Politics of the English Inquest, 1830-1926 Ian A Burney

Medical Legal Aspects of Medical Records Patricia W Iyer, Barbara J Levin, Mary Ann Shea

The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play James C Whort

Reading Constellations: Urban Modernity in Victorian Fiction Patricia McKee

And two blog posts: the fabby London Historians’ Blog and Coroners vs Police on Victorian Detectives

* Picture credits:

Weller’s 1868 map of Linton St and the North Pole: Mapco

Photograph of the North Pole: © David Anstiss and licenced for re-use under this Creative Commons licence

Morning Post report: The British Library Board, via Findmypast

Catch up with A Christmas tale:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 Part 12

Pingback: Celestina’s trial – verdict and sentence: a Christmas tale pt 18 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: New evidence against Celestina: a Christmas tale pt 14 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: A mob at the inquest: a Christmas tale pt 13 | A Rebel Hand

Inquests were held here in pubs years ago too Frances. I think the bodies were fairly quickly taken to the cold cellars of the hotels to delay decomposition.

LikeLike

Thanks, Kerryn! That makes a lot of sense.

LikeLike

You have done so much research into these intriguing tales and kept us all on the hook.

LikeLike

Thanks, Pauleen! I have to admit I’m hooked (ouch) on researching this story.

LikeLiked by 1 person