In the last episode of this true story, Celestina Sommer was in Newgate Prison awaiting her trial at another iconic bastion of London’s penal system – the Old Bailey.

Newgate (green) and the Old Bailey (red), 1850 *

The Central Criminal Court, as it was, and is, more formally known, was next to Newgate, just to the south on the street which gave it its name, Old Bailey. It was just as likely to terrify the criminal and the passing citizen as its neighbour was.

The building was designed by the same architect, George Dance, as Newgate, but in a neoclassical style and with a semi-circular wall around the front for better crowd control and privacy. The wonderful Old Bailey Online site has an image of this, and a history of the court, here.

OS map of the Old Bailey, 1953 *

The current Central Criminal Court was built on the site of the former Newgate Prison and the Sessions House (another name for the court). They were demolished in 1902 and the new building was opened in 1907.

There aren’t as many images of the Sessions House before it was pulled down as there are of Newgate, so I’m going to use contemporary written accounts to paint a word picture of what Celestina experienced on the morning of Friday, 7 March, 1856, when she was taken for trial at the Old Bailey.

The judge Celestina appeared before was Sir William Wightman, QC, a Scotsman born in 1784 and a knight and judge since 1841, 15 years before this trial. There’s a portrait of him from the 1840s here.

The newspapers loved a good murder trial. Well, in fact, most Victorians did. So it’s no surprise that they were there to see Celestina’s. Here’s the Sheffield Telegraph‘s report from the following day:

The Era, two days after the trial, had even more to say about what Celestina looked like in the dock:

The Era, two days after the trial, had even more to say about what Celestina looked like in the dock:

The journalists in these and other papers were very struck by Celestina’s young appearance and ‘absence of ferocity’. She just didn’t look like a proper murderess should. Victorians judged others on their looks even more than we do now.

The journalists in these and other papers were very struck by Celestina’s young appearance and ‘absence of ferocity’. She just didn’t look like a proper murderess should. Victorians judged others on their looks even more than we do now.

These, after all, were the days when people believed that bumps on the skull could reveal someone’s character. Faces could tell you whether someone was a criminal or not. Irish people, being poor, rowdy and foreign, had rough, monkey-like faces (prejudice has a long history) and well-behaved young women had soft, regular features. Criminals should seem coarse, violent and debauched, not small and young. That, for goodness’ sake, was what innocent women looked like.

These, after all, were the days when people believed that bumps on the skull could reveal someone’s character. Faces could tell you whether someone was a criminal or not. Irish people, being poor, rowdy and foreign, had rough, monkey-like faces (prejudice has a long history) and well-behaved young women had soft, regular features. Criminals should seem coarse, violent and debauched, not small and young. That, for goodness’ sake, was what innocent women looked like.

Whether Celestina was acting the part of a madwoman, or understandably frightened and distraught, she appeared distracted and must have been close to fainting if the attendant had to be there with a bottle of smelling salts.

What would the Old Bailey have been like on that March morning in 1856? It’s time to turn to contemporary accounts. Montagu Williams, QC, wrote in Round London: Down East and Up West in 1894, four decades later, but it still gives a feeling of the outside of the Sessions House:

Outside the Old Bailey

‘There are two entrances to the Old Bailey, one approached from the public thoroughfare, and the other approached from the court-yard of the prison. You reach the latter by passing up some stone steps which are on the right-hand side as you enter through the broad gateway. This entrance is used by the Judges, Aldermen, Sheriffs, and other officers of the Court, by counsel, and, on occasions such as the one to which I am referring, by the few privileged members of the public who have been furnished with tickets of admission. In order to prevent a crush, wooden barriers are erected at the bottom and top of the stone steps…’

Here’s James Grant, writing in The Great Metropolis in 1837:

‘The scene exhibited outside is always well worth seeing. But to be seen to the greatest advantage, one should visit the place on a Monday morning when the courts open. On the street outside, in the place leading to the New Court and in the large yard then thrown open opposite the stairs leading to the Old Court, there is always, at such a time, a great concourse of what may be called mixed society with a propriety I have seldom seen equalled in any other case. There you see both sexes, in great numbers. There are persons of all ages, of every variety of character, and in every diversity of circumstances. There are the prosecutors and the witnesses for and against the prosecution. The judges and the persons to be tried are the only parties you miss…

‘ The Old Bailey is divided into two courts. Formerly there was only one court; but for a number of years past there have been two. The one last established is called the New Court; the court which previously existed is called the Old Court. The most important cases are usually disposed of in the Old Court…’

And indeed Celestina’s trial for wilful murder was held there. So let’s go inside and have a look at the courtroom. Montagu Williams again:

Inside the Old Bailey

‘I don’t think there is a more depressing place in the world than the Old Court of the Old Bailey. There are two doors leading into the Court from the corridor. One is used by the Judges, the Aldermen and Sheriffs, and the few selected visitors, who either take their seats upon the bench or in a contiguous enclosure that looks like a huge private box. The second entrance from the corridor is used by barristers and their clerks, solicitors, and other persons having business in the Court. The centre of the chamber is occupied with seats for the members of the Bar, and below them is the solicitors’ bench. Between the Judge and the jury — both of whom command a fine view of the dock — is the witness-box.

‘Underneath the jury-box sits the usher, an individual who must enjoy very little sleep in a natural way at night, for while the trials are on he is rarely to be seen with his eyes open. Once or twice during the day, however, he rouses himself by a great effort and, in stentorian tones, shouts “Silence!” and this, generally, at a time when everything is so still that you could almost hear a pin drop.

‘At length there are the two knocks, and the Judge, the Lord Mayor, and the Sheriffs, preceded by the mace bearer, enter the crowded Court. The prisoner ascends from below into the dock, steps up to the rail, and is called upon by the Clerk of Arraigns to plead to the indictment….’

Published in 1858, two years after Celestina Sommer’s trial, The Leisure Hour, an illustrated weekly journal, described the scene:

‘It is to the Old Court, however, situated to the left of the entrance from the street, that the greatest interest attaches, because it is here that those memorable trials have taken place which have made the annals of the Old Bailey famous in the classics of crime. This Old Court is a hall of no architectural pretensions, about forty feet square, and tolerably well lighted and ventilated. Opposite the entrance is the raised seat of the judges, extending along one whole side of the apartment. Near the centre is the chief seat, with a canopy overhead, surmounted by the royal arms, and showing beneath it a gilded sword upon the crimson draped wall.

Dead Man’s Walk, the passage from Newgate to the court

‘Fronting the bench, and close to the entrance, is the dock for the prisoners, in which they stand on a raised platform with wainscoted bulwarks. The prisoners are not brought to this dock from the street and through the assembled crowds, but pass into it through an underground stone passage which connects the Old Court with the prison of Newgate. In front of the prisoner, on the broad hand-rail on which he leans, are scattered a number of sprigs of the rue plant – not to remind him, as simple people have supposed, of his rueful condition, but as an antidote to the danger of infection which the court is supposed to incur from his presence after confinement in unwholesome cells. This practice is about a century old…

‘To the left of the dock is the witness-box, and to the left of that the jury-box – an arrangement which enables the jury, as well as the judges on the bench, to see at one glance the faces both of the witnesses and the prisoners. The counsel have their seats round a table in the centre below, and to the right of the table are rows of raised seats for the accommodation of spectators, and a few benches, supposed by a fiction of the law to be free to the public, though in practice the reverse is the case. The accommodation really provided for the public is a gallery with rows of benches above the head of the prisoner, and in front of the bench of judges, admission to which is obtainable only on payment of a fee.

‘We will look in now upon this Old Court while a trial is going on. The crowd around the outer portals, and the pushing and struggling for entrance, would warn us, if we did not know it already, that an affair of more than usual interest is going forward. We elbow through the crowd and make for the lower door, but there the policemen in attendance only shake their heads at all demands for admission, and refuse to, pass a single additional person who cannot show that his presence is required within. We mount the stairs leading to the gallery, where numbers more are clustered round the doom, waiting their time to take the places of such of those within, who, under the pressure of the heat or that of hunger and thirst, shall choose to vacate them. Half an hour’s patience, and an oblation of current coin, at length procure us the privilege of attempting to force a way in…’

James Grant described the courtroom as it was two decades earlier, in 1837:

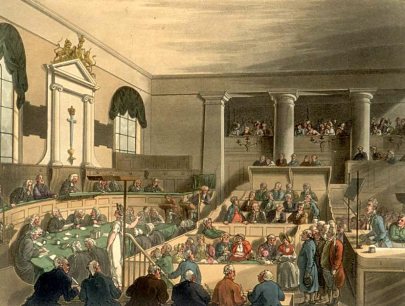

Old Bailey trial, 1808, before refitting *

‘The interior of both courts is tastefully fitted up. They have of late been re-altered and repaired at an expense of several thousand pounds. The judges in either court sit on the north side. Immediately below them are the counsel, all seated around the table. Directly opposite the bench is the bar, and above it, but a little further back, is the gallery. The jury sit, in the Old Court, on the right of the bench: in the New Court they sit on the left of the bench. The witness-box is, in both courts, at the farthest end of the seats of the jury. The reporters, in both courts, sit opposite the jury.

‘The Old Bailey courts sit from nine in the morning, till nine, ten, and sometimes eleven at night. Nine is the usual time for rising; but when a case goes on up to that hour, the courts usually sit until it is finished.’

WS Gilbert, a man better known to have had a little list of lyrics for Arthur Sullivan’s tunes, also wrote a large part of the illustrated book London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life. Before his theatrical career, he’d contemplated going into law. Unfortunately it seems that he didn’t write the sketches about the Old Bailey, the m’learned friends and the witnesses. Still, it’s worth adding some of these near-contemporary eyewitness accounts. These were written about 10 years after Celestina’s trial.

‘The bench occupies one side of the court, and the dock faces it. On the right side of the bench are the jury-box and witness-box; on the left are the seats for privileged witnesses and visitors, and also for the reporters and jurymen in waiting. The space bounded by the bench on one side, the dock on another, the jury-box on a third, and the reporters’ box on the fourth, is occupied by counsel and attorneys, the larger half being assigned to the counsel. Over the dock is the public gallery, to which admission was formerly obtained by payment of a fee to the warder. It is now free to about thirty of the public at large at one time, who can see nothing of the prisoner except his scalp, and hear very little of what is going on.

Punch’s Almanack: trial for murder mania *

‘The form in which a criminal trial is conducted is briefly as follows: The case is submitted to the grand jury, and if, on examination of one or more of the witnesses for the prosecution, they find a prima facie case against the prisoner, a “true bill” is found, and handed to the clerk of arraigns in open court. The prisoner is then called upon to plead: and, in the event of his pleading “guilty”, the facts of the case are briefly stated by counsel, together with a statement of a previous conviction, if the prisoner is an old offender, and the judge passes sentence. If the prisoner pleads “not guilty,” the trial proceeds in the following form. The indictment and plea are both read over to the jury by the clerk of arraigns, and they are charged by him to try whether the prisoner is “guilty” or “not guilty.” The counsel for the prosecution then opens the case briefly or at length, as its nature may suggest, and then proceeds to call witnesses for the prosecution. At the close of the “examination in chief” of each witness, the counsel for the defence (or, in the absence of counsel for the defence, the prisoner himself) cross-examines.

‘At the conclusion of the examination and cross-examination of the witnesses for the prosecution, the counsel for the prosecution has the privilege of summing up the arguments that support his case. If witnesses are called for the defence, the defending counsel has, also, a right to sum up; and in that case the counsel for the prosecution has a right of reply. The matter is then left in the hands of the judge, who “sums up”, placing the facts of the case clearly and impartially before the jury, pointing out discrepancies in the evidence, clearing the case of all superfluous matter, and directing them in all the points of law that arise in the case. The jury then consider their verdict, and, when they are agreed, give it in open court, and the prisoner at the bar is asked whether he has anything to say why the sentence of law shall not be passed upon him. This question is little more than a matter of form, and the judge rarely waits for an answer, but proceeds immediately to pass sentence on the prisoner…

William Ballantine, Celestina’s defence counsel *

‘To a stranger, a criminal trial is always an interesting sight. If the prisoner happens to be charged with a crime of magnitude, he has become quite a public character by the time he enters the dock to take his trial; and it is always interesting to see how far a public character corresponds with the ideal which we have formed of him. Then his demeanour in the dock, influenced, as it often is, by the fluctuating character of the evidence for and against him, possesses a grim interest for the unaccustomed spectator. He is witnessing a real sensation drama, and as the case draws to a close, if the evidence has been very conflicting, he feels an interest in the issue akin to that with which a sporting man would take in the running of a great race.

‘Then the deliberations of the jury on their verdict, the sharp, anxious look which the prisoner casts ever and anon towards them, the deep breath that he draws as the jury resume their places, the trembling anxiety, or, more affecting still, the preternaturally compressed lips and contracted brow, with which he awaits the publication of their verdict, and his great, deep sigh of relief when he knows the worst, must possess a painful interest for all but those whom familiarity with such scenes has hardened. Then comes the sentence, followed, perhaps, by a woman’s shriek from the gallery, and all is over, as far as the spectator is concerned. The next case is called on, and new facts and new faces soon obliterate any painful effect which the trial may have had upon his mind.’

Celestina had certainly ‘become quite a public character’ and the crowds in the courtroom no doubt expected a thrilling trial. Unfortunately for them, the counsel for Celestina’s defence, William Ballantine, had other ideas. He asked the Court to allow the trial to ‘stand over’ until the next session, in April, as the Morning Post reported:

Mr Justice Wightman pointed out that the trial was ‘specially fixed for that morning’. On what ground was the application for postponement made?

Mr Justice Wightman pointed out that the trial was ‘specially fixed for that morning’. On what ground was the application for postponement made?

In other words, he needed more time than the week he’d had to find out whether Celestina had been ‘insane’ when she murdered her daughter, Celestina Christmas. If she had been insane, she wouldn’t be sentenced to death. So the consequences were huge.

In other words, he needed more time than the week he’d had to find out whether Celestina had been ‘insane’ when she murdered her daughter, Celestina Christmas. If she had been insane, she wouldn’t be sentenced to death. So the consequences were huge.

The counsel for the prosecution, William Bodkin, had no objection:

The Court agreed to postpone Celestina Sommer’s trial until the April session.

The Court agreed to postpone Celestina Sommer’s trial until the April session.

It’s interesting that Bodkin picked up the ‘one possible result’ – hanging – and that a trial with such a possible end should not appear to have been hurried. He was thinking ahead, to public opinion as well as legal precedence.

And so Celestina was taken back to Newgate to prove herself insane – or not – and to wait for her final trial: for life or death.

Further reading:

The Cat’s Meat Shop: a tour of legal London

Wayward Women: Victorian England’s Female Offenders

Victorian London: just what it says. A treasure trove

Old Bailey Online

London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life, c1870, written by Henry Mayhew (author of London Labour and the London Poor) and others

* Picture credits:

Dead Man’s Walk: public domain

Punch’s Almanack: British Library Board

William Ballantine, caricature by Alfred Thompson: via Wikipedia

Newspaper reports: The British Library Board, via Findmypast

Map: Cross’s New Plan of London, 1850, via Mapco

Map: OS London/TQ, 1:2,500/ 1:1,250, 1951, via National Library of Scotland

Catch up with A Christmas tale:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15

Pingback: Another murder: a Christmas tale pt 11 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina’s life in Millbank Prison: a Christmas tale pt 22 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Will Celestina hang? A Christmas tale pt 20 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Broadside ballads about Celestina: a Christmas tale pt 19 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina’s trial – verdict and sentence: a Christmas tale pt 18 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina Sommer’s trial for murder: a Christmas tale pt 17 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: New evidence against Celestina: a Christmas tale pt 14 | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Celestina in Newgate Prison: a Christmas tale pt 15 | A Rebel Hand

Even more than today it must have been something of a circus. Somewhere I’d lost sight of just how young she was…insane or not.

LikeLike

Yes, very young, and 10 years younger when she’d had little Celestina.

You’re right – that Punch cartoon shows just what a circus it was. I can’t help thinking that a trial was more about entertainment and/or showing off than justice.

LikeLiked by 1 person