I’ve been scratching my head over this blog post. Shelley from Twigs of Yore has challenged us to write about the work one of our ancestors did and I’ve decided to stick with Nicholas Delaney because I’ve got so much documentary evidence about his life, from his trial in 1799 and arrival in Sydney Cove in 1802 onwards.

It’s finding out about what working lives were like 200 years ago that’s been the real challenge for me this January, and it’s been fascinating.

Nicholas was a landless, illiterate peasant when he got caught up in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 – a hired hand. He would have been tough and muscular then, but three years’ imprisonment and the long voyage from Cork would have wasted him.

Still, he was strong enough for Major George Johnston of the New South Wales Corps to select him to work on his own land instead of being put to Government service like so many town-bred thieves were. He knew farming, and this is how he passed the beginning of his sentence on Australia. Johnston prided himself on reforming his convicts – and feeding them lots of vegetables. Nicholas’s luck was in.

On January 26, 1808 (the 20th anniversary of the founding of the new colony), George Johnston was involved in the Rum Rebellion, Australia’s only successful military coup. Soon after that Nicholas left his service and, in October, he married Elizabeth Bayly, a free settler and something of a mystery. Family oral history has him working as a gardener (or butler! Where did that come from, I wonder) at Government House.

5 shovels and 3 tomahaws

Our first documentary evidence of his day-to-day work is on 9th November 1812, when the Acting Commissary issued him, ‘the Government Park Keeper’, with ‘5 shovels and 2 large tomahaws [sic] and 3 shovels’.

This shows that Nicholas, the rebel and convicted double murderer, was now trusted to be the overseer of a gang of labourers, a job he was to do for a while, and also to look after their tools – a big responsibility in New South Wales, where there were no mines and all metal equipment had to be brought in by ship.

His luck was in again, because the new Governor, Lachlan Macquarie, was determined to smarten Sydney up and build good roads into the interior of the colony. Nicholas Delaney was the perfect man to lead one of Macquarie’s road gangs.

A report of 1812 describes how the roadbuilders were organised:

‘They work from six in the morning to three in the afternoon, and the remainder of the day is allowed to them, to be spent either in amusement or profitable labour for themselves. They are clothed, fed, and for the most part lodged by the Government.’*

However the Bigge Report of 1822 paints a picture of unruly convicts, unsupervised, drunken and thieving. John Thomas Bigge was doing his best to discredit Macquarie.

In 1816, Nicholas was involved in two prestigious projects for the Governor in Sydney. His gang was hard at work building Mrs Macquarie’s Road, a pleasant drive round the Domain designed by Lachlan’s wife Elizabeth, and taking in her favourite viewpoint, Mrs Macquarie’s Chair.

Part of the original road Nicholas and his men built can still be seen, at Macquarie Culvert.

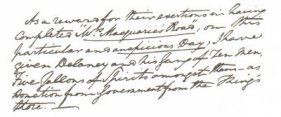

By a stroke of luck (or canny planning) they finished the entire job on her birthday, the 16th of June. Her delighted husband wrote in his diary that as a reward for completing ‘on this particular and auspicious Day‘, he would give ‘Delaney and his gang of Ten Men, five gallons of Spirits among them’. The Macquaries would not have been the only ones having a party that night.

Hardly had their hangovers gone before they were at work on a new project, ‘clearing and levelling that Piece of Ground in the Town of Sydney, adjoining the Government Domain called “Macquarie Place,” preparatory to its being enclosed by a Dwarf Stone Wall and Paling in the form of a Triangle!’ as the Governor wrote in his diary on 1st July.

The New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage recognises it as ‘one of the most historically significant urban spaces in Sydney and Australia’, but most people know it for convict architect Francis Greenway‘s obelisk.

Later that year Nicholas was promoted to Superintendent of Road Makers at the generous salary of £91.5s a year (about £63,500 today). Wealth for toil, indeed!

Nicholas’s other construction work that we know about took place outside Sydney. He may have been one of William Cox’s supervisors during the building of the Great Western Highway across the Blue Mountains. I’m still looking into this – it would be great to know by the bicentenary of Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Wentworth‘s crossing of the Blue Mountains in 2013.

We do know that after his promotion Nicholas (now ‘Mr Delaney’) began work on the Parramatta to Penrith road, conveniently close to his grant of 50 acres at Emu. The work was urgent. On 23 September 1818, the Colonial Secretary wrote to the Assistant Commissary General at Parramatta that Nicholas’s 36 men had to work ‘during the whole of each Day’ instead of being free from three o’clock, and would therefore be given one and a half times the standard rations.

Hard-working

Rations were not always available for the hard-working men, though. On 17 January 1820, Mr Delaney and the other overseers in the Parramatta area petitioned the government to complain about arrangements for issuing rations.

It was their job to collect ‘provisions… at Parramatta and occasionally tools, slops [convicts’ clothes] and other stores at Sydney’. The problem was that the Parramatta storekeeper only turned up at 1030 or 1100 in the morning to issue meat – by which time, in the summer heat, it was unfit to eat. They suggested that seven would be a better time. The Colonial Secretary answered quickly, agreeing because ‘much time is lost, to the manifest prejudice of the Public Service, as well as to the great personal inconvenience to the overseers themselves’. Not to mention the inconvenience to the hungry labourers.

By now he was being referred to as Principal Overseer, Great Western Road. But the good times were nearly over for Mr Delaney the roadbuilder.

The end of the road

Lachlan Macquarie had been sent back to Britain in December 1821, and on 12 January, 1822, while his patron was sailing away from Australia, Nicholas was ‘displaced from his situation on the Western Road’. There is no clue as to why he was removed, but the new Governor, Sir Thomas Brisbane, cut the number of convicts working on the roads. Fewer gangs need fewer overseers.

There is another possibility. At some stage Nicholas broke his thigh. If this had happened while he was working on the Western Highway he would no longer be able to supervise his gangs.

But perhaps the simplest reason is that he had applied to the Evan Magistrates for a spirits licence in December 1821, and they had found him and Elizabeth ‘proper persons’ to run a pub in ‘his Dwelling House on the Western Road’. Whether he had realised that his career on the roads was over when Macquarie left, or whether it was a coincidence, I don’t know. But from now on, Mr Delaney was an innkeeper and a farmer.

* Wannan, Bill (ed), The Australian, Melbourne, 1954, p 135

Pingback: Ulva, Lachlan Macquarie’s birthplace | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: My first Australian ancestor (Australia Day Challenge 2013) | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Australia Day Challenge 2014: C’mon Aussie | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: Back to Blog – death and renewal | A Rebel Hand

Pingback: The Factory above the Gaol – women convicts in 1818 | A Rebel Hand

I think it did – after the misery of his imprisonment, Australia gave him a new chance and he grabbed it. His life was certainly better than it would have been if he’d never been convicted and transported.

Thanks again setting the Australia Day challenge – it was an inspiration and I’ve enjoyed reading everyone’s contributions.

LikeLike

Sounds like being convicted worked out well for him! I enjoyed the details and context you put together for his story. I wouldn’t have thought about things like all the metal tools having to come in by ship. Thanks for your contribution!

LikeLike

That must be so amazing to have such a close connection to the whole of the Domain area – it is a very special place. You write the story of Delaney’s early working life very well.

LikeLike

Thank you, Alex. I’m really hoping to visit the Domain in the bicentenary year, 2016 – how exciting that would be!

LikeLike

What a fantastic story. All I want to know is how he

broke his thigh.

LikeLike

Thanks, Sharon. Infuriatingly, I have no idea how he broke his thigh and it just gets referred to as something that happened a while ago, very matter-of-fact. An accident at work? A fall? I’d love to know…

LikeLike

What a comprehensive post. I enjoyed reading about Mr Delaney and his life in Sydney’s early days. Thanks for sharing his story.

LikeLike

Thank you, Jill. I enjoyed researching it hugely. There’s so much more information about now than when I first started looking at his life – I had to force myself not to include a lot. Maybe another post?

LikeLike

A great post. I enjoyed reading it. I focused on a part of my family that was a surprise in finding they migrated to Tasmania in 1822.

LikeLike

Thanks, Julie. I enjoyed your post – an the way you described that moment of surprise discovery. It’s a really intriguing story and I hope you find more in Australia!

LikeLike

What an intriguing story. Not only was he a very fortunate convict but it seems his descendant has been too, with lots of information available on him, and you’ve added so much dimension to his life with your research. Nicholas aka Mr Delaney certainly did his best in his new country, settling in and making a solid life for himself and family. Thanks for an engaging story.

LikeLike

Thanks, Pauleen. I’ve been very lucky, and before my mother and I started on Nicholas’s trail our cousin Antoinette Sullivan had done an enormous amount of research on him. Other cousins have been rich sources of information, too, and I’m very grateful to them all.

Nicholas seems to have decided to settle down and get the most he could from his new life. He wasn’t a total goody-goody, though, as I hope to show one day…

LikeLike